By Carlos Caminada, Shruti Singh and Jeff Wilson

Oct. 27 (Bloomberg) -- The credit crunch is compounding a profit squeeze for farmers that may curb global harvests and worsen a food crisis for developing countries.

Global production of wheat, the most-consumed food crop, may drop 4.4 percent next year, said Dan Basse, president of AgResource Co. in Chicago, who has advised farmers, food companies and investors for 29 years. Harvests of corn and soybeans also are likely to fall, Basse said.

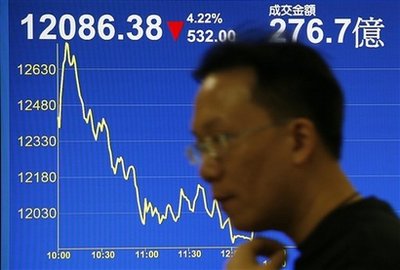

Smaller crops risk reviving prices of farm commodities that sank from records in 2008 after a six-year rally that spurred inflation and sparked riots from Asia to the Caribbean. Futures contracts on the Chicago Board of Trade show wheat will jump 16 percent by the end of 2009, corn will rise 15 percent and soybeans will gain 3 percent.

``The credit situation is worrying even the biggest and best farmers,'' said Brian Willot, 36, a former University of Missouri commodity analyst who now grows soybeans on 2,000 acres in Brazil. ``For the financially weak, credit has dried up completely. For the strong, credit has been delayed and interest rates are higher.''

The number of hungry around the world is at risk of increasing as the financial crisis cuts investment in agriculture and crops, said Abdolreza Abbassian, secretary of the Intergovernmental Group on Grains at the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome. The total increased by 75 million last year to 923 million, the UN estimates.

Brazil Squeeze

``The net effect of the financial crisis may end up being lower planting, lower production,'' Abbassian said. ``More people will go hungry.''

In Brazil, the world's third-biggest exporter of corn after the U.S. and Argentina, production may fall more than 20 percent because farmers can't get loans to buy fertilizer, said Enori Barbieri, a National Corn Producers Association vice president. The nation's coffee harvest, the world's largest, may drop 25 percent for the same reason, said Lucio Araujo, commercial director at farmer cooperative Cooxupe, located in Guaxupe.

Borrowing costs increased and farmers struggled to get loans after the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression made banks and grain processors, including Cargill Inc. and Archer Daniels Midland Co., less tolerant of risk.

Minnetonka, Minnesota-based Cargill and Decatur, Illinois- based Archer Daniels, the world's largest grain processors, are among the crop buyers to halt financing for growers in Brazil, said Eduardo Dahe, who represents the companies as president of the National Association of Fertilizer Distributors.

Lending `Stopped'

Processors usually cover half the financing needs of farmers by accepting part of the future crop as payment. ``No one is doing it,'' Dahe said. ``It's stopped.''

In Russia, loan rates for farmers have jumped by half in some cases to more than 20 percent in the past few months, Arkady Zlochevsky, president of the Russian Grain Union, said in an interview earlier this month.

While the credit squeeze gripping emerging markets has yet to hurt the U.S., the risk remains, Agriculture Secretary Ed Schafer said Oct. 1.

``We certainly could see tight credit having an effect on agricultural production,'' Schafer said in Washington. ``The costs of farming operations today are huge, and that backs up to the banks that have balance sheets that are tight, it backs up to elevators that have credit stretched out.''

Farm Incomes

To be sure, farmers in the U.S., the world's largest grain exporter, may have enough cash to avoid production cuts through next year because of this year's record profits.

Net farm income will rise 10 percent this year to $95.7 billion, the U.S. Agriculture Department estimated Aug. 28. While farm debt jumped 7.7 percent last year to $211 billion, the total is 9.6 percent of assets, a ratio that the government forecast on Aug. 28 will drop to 8.9 percent this year, the lowest level since at least 1960, the earliest data available.

``I don't see the crisis'' for U.S. farmers, said Corny Gallagher, who helps oversee $20 billion in global agribusiness and food-product loans for Bank of America Corp. in Sacramento, California. ``While commodity prices are down from their peak, they are still relatively high.''

Warning signs are appearing.

`Deteriorating' Conditions

Global inventories of corn, wheat and soybeans before the harvest in the Northern Hemisphere next year will be the second- lowest since 1974, enough for 67 days of consumption, compared with 144 days of supplies in 1986, U.S. data show.

``Stockpiles are going to be extremely tight,'' said AgResource's Basse. ``The world cannot afford any dislocation in production next year, or there will be a real shortage.''

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City said Aug. 15 that credit conditions in the second quarter, the most recent data available, ``showed signs of deterioration'' in the seven-state region that includes Kansas, the biggest U.S. producer of winter wheat. Loan-repayment rates fell for the first time since 2006 as wheat slid 7.6 percent in the quarter. Wheat lost another 41 percent since then.

``This year is going to be the best year ever and now we are looking at the potential to give it all back in 2009 if prices don't rise above the expected cost of production,'' said Mark Kraft, 49, who grows corn and soybeans in Normal, Illinois. ``You have to hope that fertilizer, seed and land rents come down and the price of corn improves.''

Lower Prices, Higher Costs

Wheat fell to $5.1625 a bushel on the Chicago Board of Trade on Oct. 24, touching a 16-month low of $4.965. On Feb. 27, it reached a record $13.495. Corn fell 7.5 percent last week and touched a one-year low of $3.64 a bushel today, compared with a peak of $7.9925 on June 27. Soybeans fell 4.4 percent last week to $8.67 a bushel and are down 47 percent from a record $16.3675 on July 3. Rough-rice futures are down 41 percent to $14.685 per 100 pounds from $25.07, the highest ever, on April 24.

One 80,000-kernel bag of Monsanto Co. corn seed, enough for about 2.5 acres, rose 45 percent this year to $320, the same amount Midwest tenant farmers paid to rent an acre of land, Kraft said. A gallon of diesel for tractors averaged $4.47 in the third quarter, up 51 percent from a year earlier, according to AAA, the largest U.S. motorist organization.

The value of the collateral farmers use to secure loans -- crops and land -- is diminishing. Lenders are demanding more equity for farm loans used to run operations or acquire land and equipment.

``We need two to three times the amount of money we used to need with the same collateral,'' said Bo Stone, 37, a seventh- generation farmer in Rowland, North Carolina. ``It means we have way more risk than we've ever had. This is a time where one bad crop year, with the amount of money and input tied up, could potentially cost you your equipment, land and livelihood.''

To contact the reporters on this story: Carlos Caminada in Sao Paulo at at ccaminada1@bloomberg.net; Shruti Date Singh in Chicago at ssingh28@bloomberg.net; Jeff Wilson in Chicago at jwilson29@bloomberg.net.

Read more...